The Lost Princess of Oz is, at its heart, a tale of truth, deception and illusion, taking a subtle look at the methods used by rulers to maintain control. Nearly every ruler and authority figure in this book tells a lie of one kind or another, actively building a net of deception. Those who do not are oddly powerless. Throw in a classic quest story, a hint of mystery, and lessons on the differences between reality and illusion, and you have one of the better of the latter Oz books.

Oh, and a village of gun-toting teddy-bears. What’s not to love?

The book begins with the sudden and inexplicable disappearance of Princess Ozma, ruler of Oz. (Perhaps not surprisingly I regard this as a plus.) As Dorothy and her friends Betsy Bobbin and Trot search for their missing Ruler, a few more thefts are discovered: the great Book of Records owned by Glinda the Sorceress; all of Glinda’s magical tools; the Wizard’s bag of tricks; and a golden dishpan decorated with diamonds. The dishpan doesn’t exactly sound practical, but its distressed owner assures us that it makes amazingly good cookies.

The now familiar Oz characters gather in the Emerald City, horrified at their loss. For the first time, we have a genuine explanation for why the inhabitants of Oz have been so willing to put up with all of the previous examples of Ozma fail: the other potential rulers are equally if not more inept. Glinda is at a loss; the Wizard has failed to notice that his magic bag of tricks is missing. It falls to Dorothy—only a kid—to suggest a practical response: searching.

Glinda organizes some exceedingly mismatched search groups. Quite a few characters choose to join Dorothy’s group, which makes it rather unwieldly for narrative purposes. (This continued to be a problem in all later Oz books, where Baum apparently felt the need to give nearly every beloved character at least one speaking line. Although this undoubtedly pleased fans, it also slowed down the narrative.) Most of her search group ends up having little to do, except, oddly enough, for the still utterly nonchalant Button-Bright.

To find Ozma, they must visit the usual assortment of strange hidden cities. Here matters get intriguing, since each and every one of these cities is ruled through some form of deception. The city of the Thists, for instance (they eat thistles) is not only protected by the deceptive shifting environment that surrounds it, but is governed by a High Coco-Lorum, an absolute ruler. Knowing that his subjects would hate and resent a king, he has changed his title—but continues to make all laws to suit himself. The Herku of the next city appear as fragile as paper—and can crush stones with their bare hands. Their strength comes from a compound of pure energy, a compound they hide from their slaves, who are giants. Hiding the compound allows them to keep the giants under control—and to occasionally toss a giant or two out a window. These deceptions even extend into the generally peaceful teddy bear kingdom, where the Lavender Bear lies regularly, as a matter of form, to keep the peace.

Critically, the lies work. Meanwhile, the ever truthful Ozma (whatever her other faults) finds herself utterly powerless.

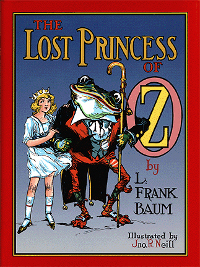

This theme continues with the introduction of the Frogman, a giant and mostly ignorant talking frog (even his name is not entirely truthful) who has convinced the Yips, and to an extent himself, that he is one of the wisest, if not the wisest, creatures in all of Oz. The Yips, believing this, have made him their chief ruler and adviser; it comes as a decided shock to the Frogman and Cayke, a Yip, to find that the outside world does not share this opinion. When the Frogman bathes in the Truth Pond, however, he is forced to examine his own self-deceptions.

He’s not the only one who has to study deception versus reality. To find Ozma, Dorothy and the gang must learn the difference between illusion and reality, and the deceptiveness of appearances, as they move through a series of traps set by a sorcerer, and try to deduce Ozma’s location. In yet another twist on the theme, the Lavender Bear’s magic allows him to do illusions—illusions that show the truth. And the animals have several conversations about appearance versus reality as they argue over which of them—Hank, the Woozy, the Cowardly Lion, Toto or the Sawhorse—is the most beautiful.

The book is not without its flaws. I was displeased to see the return of the deux ex machina Magic Belt, especially given that every other magical item of Oz was stolen. So why not that one? The usual inconsistencies and minor detours abound, along with yet another example of how the Tin Woodman’s relentless focus on kindness can result in a potentially serious miscarriage of justice, as in Patchwork Girl. A side plot about Toto’s supposedly stolen growl gets annoying.

And, oh yes, the usual Ozma fail—even in a book where she is largely completely absent. The supposedly powerful fairy is knocked out by a scarf. A simple scarf thrown over her eyes. Afterwards, she weeps and scolds her kidnapper. That’s it. Literally. I grant that she might not have been able to stop her later transformation, but surely she could have kicked? Yelled? Darted out of the way? Whispered a magical work and turned invisible? Something?

Horrifying note: the book starts with “This book is dedicated to my granddaughter Ozma Baum.” I get that the family was proud of Baum’s achievements, but how do I put this politely? UGH.

Mari Ness needs a lot of coffee to distinguish between appearance and reality. She lives in central Florida.

Button Bright takes “laid back” to an extreme in this book, even for him. Also willful obliviousness.

This was always my favorite of the later Oz books. Not sure why.

Might have something to do with most of the magic tools they usually use being unavailable. That added some fun.

Ozma Baum Mantele, the dedicatee of this book, died just a little over ten years ago. She was the last of the Baum family to have known L. Frank Baum personally, although she was still quite young when he died. She struggled for many years with her first name and would talk about how she couldn’t be sure whether people were true friends or just wanted to be associated with her because of her name. After a while, she grew to accept it.

By the way, Ozma’s recently born great-grandson is named Oz.

Ozma demonstrates quite a lot of magic in the three Oz books L. Frank Baum wrote after this one, but up to this point he hadn’t presented her as a powerful magician. A fairy with some natural powers, yes. (And when she first appeared, not even that.) Owner of the Magic Picture and Magic Belt, yes, but she didn’t wear the belt all the time.

Oz fan and writer David Hulan has theorized that the trouble of being kidnapped prompted Ozma to develop her natural powers and magical knowledge, making her the powerful fairy we know from the subsequent books.